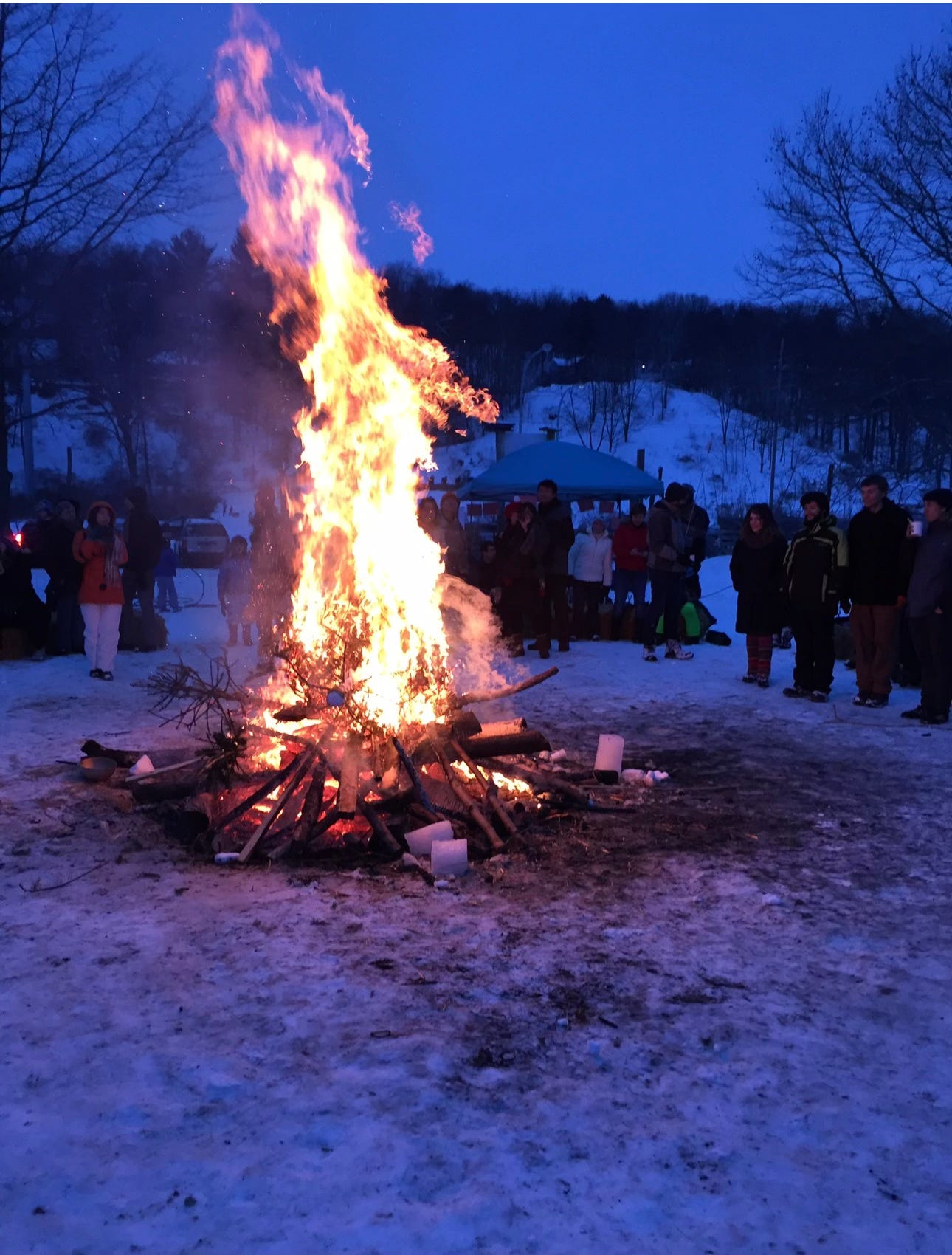

How I lived a childhood in the snow. / Hail the winter days after dark.

— “January Hymn,” The Decemberists

Chionophile (noun): Any organism that loves the snow and can thrive in winter conditions. From the ancient Greek χῐών (khiṓn; snow).

Where I live, in Ithaca, New York, we’ve had snow for about a week this winter. We’ve even had a couple days of bitter cold. This used to be normal here, but now it’s noteworthy. The temperature is warming into the 40s as I write, the valley filled with rain and fog.

Snow is my element (water, too.) Just as people with seasonal affective disorder need the sun, I need the snow. Ideally for weeks and months, but any is better than none.

I don’t know if it’s because my people come from Scandinavia and north central Europe, or because I grew up in West Michigan, where the lake effect snow is (still, sometimes) abundant and thrilling. In the 1970s and 80s, snow covered the ground in Michigan from November to April. A child, I spent those months sledding, ice skating on ponds, cross-country skiing, building snow forts, playing in the woods, and exploring the ice caves that sometimes formed on Lake Michigan. They looked like huge waves that had leapt up and frozen in midair. Neighbors flooded and froze parts of their yard so we could play ice hockey (the only team sport I was any good at, because I could stay up on my skates). Snow days home from school were plentiful, but more common were dark mornings in the single digits waiting for the school bus under a street lamp. After one storm that kept us from school, I could strap on my skates and skate our driveway and sidewalk because they were covered in inches of smooth ice.

We all wore snowmobile suits and moon boots, cherry chapstick, long underwear, and double layers of socks. Ski hats. Waterproof mittens that attached to our jackets with little clips so they wouldn’t get lost. Lots of acrylic, back in the day; synthetic fleece hadn’t been invented yet.

When it snowed and things weren’t plowed yet, my dad would drive my sister and me to a big empty parking lot at night, at an office complex or a church, and do doughnuts with the car, spinning round where we wouldn’t hit anything. When the parking lots were plowed, we climbed the huge piles of snow, several times our height, and declared ourselves king of the mountain. We made snow angels, back when a thickly-clad child under ten could fearlessly drop back into the snow and land without hurting herself, waving her arms and legs and catching snowflakes on her tongue. When it was time to come inside, we would get hot chocolate with mini-marshmallows, or chili, chicken soup, baked potatoes.

By the time I was a teen, you could go and rent a hot tub by the hour, and they were outdoors, and you could move from the tub to rolling in the snow and then back into the tub. One of my favorite memories of doing this was in Ann Arbor, just after college, the day I took my GRE, then stumbled over to the Michigan Theater to watch “Three Colors: Blue,” by Krzysztof Kieślowski, starring the luminous Juliette Binoche. The movie was depressing as hell, and satisfying for that. After, I met friends at a hot tub place for an hour or two, and then we all went out for Ethiopian food for dinner. A perfect day for the ambitious scholar, culture hound, and hedonist I was at the time.

After the GRE and graduate school applications, I moved to Slovakia. That was five years after the Berlin Wall came down, after the Velvet Revolution, and the year after Czechoslovakia split into two nations. I lived in a town in the Oravská vrchovina mountains, across the border from Poland—and, as I learned only recently, mere 100s of kilometers from one of my ancestral homes in Poland. (I also have ancestors from around Prague, and from Ukraine.) The winter there was very cold—mountain cold—and sunny, with bright aquamarine sky. I walked from my dorm up the square to the gymnázium where I taught, perhaps a 15 minute walk, dressed in warm clothes, the snow crunching under my feet. That walk, its quiet splendor and arresting cold, remains clearly imprinted in my memory. I was very happy.

In the late 1990s, in Ithaca, it sometimes snowed so that we could cross-country ski from our front door through the streets and on the frozen creek. That hasn’t happened in years. There was also a weekend at a farm in the Adirondacks with friends, where we would ski to the sauna, take a sauna, and then ski, laughing and naked, back to the house, wood stoves in both places burning.

I’ve since sold my skis.

I dread a future without snow, this essential soul food of mine. I need the cold, the dark, and the quiet. Snow slows things down. The furious pace of our modern lives can’t continue when it snows. Maybe that’s why it makes us feel like children again. And the quiet? Do you remember the hush of snow-covered land?

To me, snow in winter signals that all is right with the world; its absence unsettles and unmoors me. Warm winters feel ominous. I know that even when it’s snowing where I live, the earth is still warming. But it soothes my animal body into feeling that all is well.

If we leave Ithaca after my spouse retires, it won’t be for Florida or Arizona or Costa Rica. You’ll find us in the north country somewhere, in a place where even in summer the lakes are cold and, I fervently hope, it still snows.

Wow... this went all the way in. I’m a native Ithacan, living in Connecticut. Thank you, Sara, for reminding me of the refreshing, icy subzero cold, the snowstorms, the opportunities to play, dig, climb, ski, snowshoe, walk... sometimes in the downtown streets... solitary as a snow leopard. I grieve the loss of snow and cold, too. Nothing feels quite right about our winters now....

So glad you're writing again, dear Sara. I need your words in my heart and mind.

Thank you for this love letter to snow.